Moses Get Ready to Part the Seas Again Cause Shit Is About to Get Wet ïâ»â¿

| Robert Moses | |

|---|---|

Robert Moses with a model of his proposed Battery Bridge | |

| Built-in | (1888-12-18)December xviii, 1888 New Haven, Connecticut, US |

| Died | July 29, 1981(1981-07-29) (aged 92) Due west Islip, New York, US |

| Alma mater | Yale Academy (BA) Wadham College, Oxford (LLB, MA) Columbia University (PhD) |

| Political party | Independent Republican[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Sims (m. 1915; died 1966) Mary Alicia Grady (grand. 1966) |

| Children | 2 |

| Notes | |

| [2] [three] | |

Robert Moses (Dec 18, 1888 – July 29, 1981) was an American public official who worked mainly in the New York metropolitan area. His decisions favoring highways over public transit helped create the mod suburbs of Long Island. Although he was not a trained civil engineer,[a] Moses'due south programs and designs influenced a generation of engineers, architects, and urban planners nationwide.[4]

Moses held upward to 12 official titles simultaneously, including New York City Parks Commissioner and Chairman of the Long Island Land Park Commission,[5] but was never elected to any public role. He ran only once, as the Republican nominee for Governor of New York in 1934, and lost in a landslide. All the same, he created and led numerous semi-autonomous public authorities, through which he controlled millions of dollars in acquirement and directly issued bonds to fund new ventures with little or no input or oversight from outside sources. Every bit a result of Moses'south piece of work, New York has the United states of america' greatest proportion of public benefit corporations, which remain the primary driver of infrastructure building and maintenance and business relationship for much of the state's debt vehicles that maintain its sustainability.

Moses's projects were considered economically necessary past many contemporaries later on the Cracking Depression. Moses led the structure of New York campuses for the 1939 and 1964 Globe's Fairs and helped persuade the United nations to locate its headquarters in Manhattan instead of Philadelphia. Moses's reputation for efficiency and nonpartisan leadership was damaged by Robert Caro'south Pulitzer-winning biography The Power Broker (1974), which defendant Moses of a lust for power, questionable ethics, vindictiveness, and racism.[6] In Moses's urban planning of New York, he primarily bulldozed homes with Black and Latino residents to brand way for parks, chose the middle of minority neighborhoods equally the location for highways,[vii] and deliberately designed bridges on the parkways connecting New York City to beaches on Long Isle to be too depression for buses from the inner city to access the beaches.[half-dozen] Some reviews of Moses'southward career are critical of characterizing Moses as a racist and opponent of mass transportation, noting a more complex situation with respect to span height and positive contributions Moses made to minority communities.[eight]

Early on life and rise to ability [edit]

Moses was built-in in New Oasis, Connecticut, to German Jewish parents, Bella (Silverman) and Emanuel Moses.[9] He spent the first nine years of his life living at 83 Dwight Street in New Oasis, ii blocks from Yale University. In 1897, the Moses family unit moved to New York City,[10] where they lived on East 46th Street off Fifth Avenue.[11] Moses's father was a successful section store owner and real estate speculator in New Oasis. In order for the family to motility to New York City, he sold his real estate holdings and store, then retired.[10] Moses's mother was active in the settlement movement, with her own love of building. Robert Moses and his blood brother Paul attended several schools for their elementary and secondary education, including the Dwight Schoolhouse and the Mohegan Lake Schoolhouse, a military university near Peekskill.[12]

After graduating from Yale Higher (B.A., 1909) and Wadham College, Oxford (B.A., Jurisprudence, 1911; Grand.A., 1913), and earning a Ph.D. in political science from Columbia University in 1914, Moses became attracted to New York Metropolis reform politics.[13] A committed idealist, he adult several plans to rid New York of patronage hiring practices, including being the lead author of a 1919 proposal to reorganize the New York country government. None went very far, only Moses, due to his intelligence, caught the discover of Belle Moskowitz, a friend and trusted advisor to Governor Al Smith.[14] When the state Secretarial assistant of State'due south position became appointive rather than constituent, Smith named Moses. He served from 1927 to 1929.[xv]

Moses rose to power with Smith, who was elected equally governor in 1922, and ready in move a sweeping consolidation of the New York Country government. During that period Moses began his commencement foray into large scale public work initiatives, while drawing on Smith's political power to enact legislation. This helped create the new Long Island State Park Committee and the State Council of Parks.[16] In 1924, Governor Smith appointed Moses chairman of the State Council of Parks and president of the Long Island Country Park Commission.[17] This centralization immune Smith to run a regime later on used every bit a model for Franklin D. Roosevelt'due south New Deal federal authorities. Moses as well received numerous commissions that he carried out efficiently, such as the development of Jones Beach Land Park. Displaying a strong control of police force likewise every bit matters of engineering science, Moses became known for his skill in drafting legislation, and was called "the best bill drafter in Albany".[4] At a fourth dimension when the public was accustomed to Tammany Hall abuse and incompetence, Moses was seen every bit a savior of government.[xiv]

Presently subsequently President Franklin D. Roosevelt's inauguration in 1933, the federal government establish itself with millions of New Deal dollars to spend, withal states and cities had few projects ready. Moses was one of the few local officials who had projects shovel ready. For that reason, New York Metropolis was able to obtain pregnant Works Progress Administration (WPA), Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and other Depression-era funding. Ane of his most influential and longest-lasting positions was that of Parks Commissioner of New York Urban center, a role he served from January 18, 1934, to May 23, 1960.[18]

Offices held [edit]

The many offices and professional titles that Moses held gave him unusually wide power to shape urban development in the New York metropolitan region. These include, according to the New York Preservation Archive Projection:[19]

- Long Island State Park Commission (President, 1924–1963)

- New York State Council of Parks (Chairman, 1924–1963)

- New York Secretarial assistant of State (1927–1928)

- Bethpage State Park Potency (President, 1933–1963)

- Emergency Public Works Commission (Chairman, 1933–1934)

- Jones Beach Parkway Authorization (President, 1933–1963)

- New York Metropolis Department of Parks (Commissioner, 1934–1960)

- Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (Chairman, 1934–1981)

- New York City Planning Commission (Commissioner, 1942–1960)

- New York Land Power Dominance (Chairman, 1954–1962)

- New York'southward World Fair (President, 1960–1966)

- Function of the Governor of New York (Special Advisor on Housing, 1974–1975)

Influence [edit]

During the 1920s, Moses sparred with Franklin D. Roosevelt, then head of the Taconic State Park Commission, who favored the prompt construction of a parkway through the Hudson Valley. Moses succeeded in diverting funds to his Long Island parkway projects (the Northern State Parkway, the Southern Country Parkway and the Wantagh Land Parkway), although the Taconic Country Parkway was later completed besides.[20] Moses helped build Long Isle's Meadowbrook State Parkway. It was the first fully divided express admission highway in the earth.[21]

Moses was a highly influential figure in the initiation of many of the reforms that restructured New York state's authorities during the 1920s. A 'Reconstruction Commission' headed by Moses produced a highly influential report that provided recommendations that would largely be adopted, including the consolidation of 187 existing agencies under eighteen departments, a new executive budget system, and the four-twelvemonth term limit for the governorship.[22]

WPA swimming pools [edit]

During the Depression, Moses, along with Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, was especially interested in creating new pools and other bathing facilities, such equally those in Jacob Riis Park, Jones Beach, and Orchard Embankment.[23] [24] He devised a list of 23 pools around the urban center.[25] [26] The pools would be built using funds from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a federal agency created as part of the New Deal to gainsay the Depression'southward negative effects.[24] [27]

11 of these pools were to be designed meantime and open in 1936. These comprised 10 pools at Astoria Park, Betsy Head Park, Crotona Park, Hamilton Fish Park, Highbridge Park, Thomas Jefferson Park, McCarren Park, Cherry Hook Park, Jackie Robinson Park, and Sunset Park, too as a standalone facility at Tompkinsville Pool.[28] Moses, forth with architects Aymar Embury II and Gilmore David Clarke, created a common blueprint for these proposed aquatic centers. Each location was to have distinct pools for diving, swimming, and wading; bleachers and viewing areas; and bathhouses with locker rooms that could exist used as gymnasiums. The pools were to have several mutual features, such equally a minimum 55-thousand (fifty yard) length, underwater lighting, heating, filtration, and low-toll construction materials. To fit the requirement for inexpensive materials, each building would exist built using elements of the Streamline Moderne and Classical architectural styles. The buildings would also exist near "condolement stations", additional playgrounds, and spruced-up landscapes.[28] [29]

Construction for some of the 11 pools began in Oct 1934.[30] Past mid-1936, 10 of the 11 WPA-funded pools were completed and were existence opened at a rate of one per calendar week.[24] Combined, the facilities could accommodate 66,000 swimmers.[31] [32] The xi WPA pools were considered for New York City landmark status in 1990.[33] Ten of the pools were designated as New York Urban center landmarks in 2007 and 2008.[34]

Moses allegedly fought to keep African American swimmers out of his pools and beaches. One subordinate remembers Moses saying the pools should be kept a few degrees colder, allegedly because Moses believed African Americans did not like common cold water.[35]

Water crossings [edit]

Triborough Bridge [edit]

Part of the Triborough Span (left) with Astoria Park and its pool in the center

Although Moses had power over the construction of all New York City Housing Authority public housing projects and headed many other entities, it was his chairmanship of the Triborough Bridge Authorisation that gave him the most ability.[xiv]

The Triborough Span (later officially renamed the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge) opened in 1936, connecting the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens via three separate spans. Linguistic communication in its Authority's bond contracts and multi-year Commissioner appointments made it largely impervious to pressure from mayors and governors. While New York Urban center and New York State were perpetually strapped for money, the bridge'due south toll revenues amounted to tens of millions of dollars a yr. The Dominance was thus able to raise hundreds of millions of dollars by selling bonds, a method likewise used by the Port Dominance of New York and New Jersey[36] to fund large public construction projects. Toll revenues rose quickly as traffic on the bridges exceeded all projections. Rather than pay off the bonds, Moses used the revenue to build other toll projects, a cycle that would feed on itself.[37]

Brooklyn–Bombardment link [edit]

In the belatedly 1930s a municipal controversy raged over whether an additional vehicular link betwixt Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan should be congenital as a bridge or a tunnel. Bridges tin can be wider and cheaper to build, but taller and longer bridges utilize more ramp space at landfall than tunnels do.[14] A "Brooklyn Bombardment Span" would accept decimated Battery Park and physically encroached on the financial commune, and for this reason, the bridge was opposed by the Regional Plan Association, historical preservationists, Wall Street financial interests, property owners, diverse high society people, construction unions, the Manhattan borough president, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, and governor Herbert H. Lehman.[14] Despite this, Moses favored a span, which could both behave more automobile traffic and serve as a higher visibility monument than a tunnel. LaGuardia and Lehman every bit usual had little money to spend, in part due to the Great Depression, while the federal government was running low on funds after recently spending $105 meg ($ane.8 billion in 2016) on the Queens-Midtown Tunnel and other City projects and refused to provide any additional funds to New York.[38] Awash in funds from Triborough Bridge tolls, Moses accounted that money could only be spent on a bridge. He as well clashed with the primary engineer of the project, Ole Singstad, who preferred a tunnel instead of a bridge.[14]

Just a lack of a cardinal federal approval thwarted the bridge projection. President Roosevelt ordered the War Department to affirm that bombing a bridge in that location would block East River admission to the Brooklyn Navy Thou upstream. Thwarted, Moses dismantled the New York Aquarium on Castle Clinton and moved it to Coney Island in Brooklyn, where it grew much bigger. This was in credible retaliation, based on specious claims that the proposed tunnel would undermine Castle Clinton's foundation. He likewise attempted to raze Castle Clinton itself, the historic fort surviving but subsequently beingness transferred to the federal government.[xiv] Moses now had no other pick for a trans-river crossing than to build a tunnel. He deputed the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel (now officially the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel), a tunnel connecting Brooklyn to Lower Manhattan. A 1941 publication from the Triborough Span and Tunnel Say-so claimed that the government had forced them to build a tunnel at "twice the cost, twice the operating fees, twice the difficulty to engineer, and one-half the traffic," although engineering studies did not support these conclusions, and a tunnel may take held many of the advantages Moses publicly tried to attach to the bridge selection.[14]

This had non been the first time Moses pressed for a bridge over a tunnel. He had tried to upstage the Tunnel Authority when the Queens-Midtown Tunnel was being planned.[39] He had raised the same arguments, which failed due to their lack of political support.[39]

Post-war influence of urban development and projects [edit]

Moses's power increased after World War Ii after Mayor LaGuardia retired and a series of successors consented to nearly all of his proposals. Named urban center "structure coordinator" in 1946 by Mayor William O'Dwyer, Moses became New York City's de facto representative in Washington. Moses was besides given powers over public housing that had eluded him nether LaGuardia. When O'Dwyer was forced to resign in disgrace and was succeeded past Vincent R. Impellitteri, Moses was able to assume even greater behind-the-scenes control over infrastructure projects.[14] I of Moses's first steps later Impellitteri took office was halting the creation of a citywide Comprehensive Zoning Programme underway since 1938 that would take curtailed his nearly unlimited power to build within the city and removed the Zoning Commissioner from ability in the process. Moses was besides empowered as the sole authority to negotiate in Washington for New York Metropolis projects. Past 1959, he had overseen construction of 28,000 apartment units on hundreds of acres of land. In clearing the country for high-rises in accordance with the towers in the park concept, which at that fourth dimension was seen equally innovative and beneficial by leaving more grassy areas betwixt high-rises, Moses sometimes destroyed almost as many housing units equally he built.[14]

From the 1930s to the 1960s, Robert Moses was responsible for the construction of the Triborough, Marine Parkway, Throgs Neck, Bronx-Whitestone, Henry Hudson, and Verrazzano-Narrows Bridges. His other projects included the Brooklyn-Queens Freeway and Staten Island Expressway (together constituting nearly of Interstate 278); the Cantankerous-Bronx Expressway; many New York Country parkways; and other highways. Federal involvement had shifted from parkway to expressway systems, and the new roads mostly conformed to the new vision, lacking the landscaping or the commercial traffic restrictions of the pre-state of war highways. He was the mover behind Shea Stadium and Lincoln Centre, and contributed to the United nations headquarters.[14]

Moses had influence outside the New York area equally well. Public officials in many smaller American cities hired him to design state highway networks in the 1940s and early on 1950s. For case, Portland, Oregon hired Moses in 1943; his plan included a loop around the city center, with spurs running through neighborhoods. Of this programme, merely I-405, its links with I-5, and the Fremont Bridge were congenital.[xl]

Moses knew how to drive an automobile, but he did non have a valid driver's license.[41] Moses'due south highways in the first one-half of the 20th century were parkways—curving, landscaped "ribbon parks" that were intended to be pleasures to travel as well as "lungs for the city"—though the Mail–World War II economical expansion and notion of the automotive city brought freeways, nearly notably in the form of the vast, federally funded Interstate Highway System network.[xiv]

Brooklyn Dodgers [edit]

When Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley sought to replace the outdated and battered Ebbets Field, he proposed building a new stadium near the Long Isle Rail Road on the corner of Atlantic Avenue and Flatbush Avenue (next to the present-twenty-four hours Barclays Centre, home of the NBA Brooklyn Nets). O'Malley urged Moses to help him secure the belongings through eminent domain, only he refused, having already decided to build a parking garage on the site. Moreover, O'Malley'due south proposal — to have the metropolis larn the belongings for several times as much as he had originally said he was willing to pay — was rejected by both pro- and anti-Moses officials, newspapers, and the public as an unacceptable government subsidy of a private business concern enterprise.[42]

Moses envisioned New York's newest stadium beingness congenital in Queens' Flushing Meadows on the old (and equally it turned out, future) site of the World's Fair, where it would eventually host all 3 of the city'southward major league teams of the twenty-four hour period. O'Malley vehemently opposed this plan, citing the squad'southward Brooklyn identity. Moses refused to budge, and after the 1957 flavour the Dodgers left for Los Angeles and the New York Giants left for San Francisco.[14] Moses was later able to build the 55,000-seat multi-purpose Shea Stadium on the site; construction ran from October 1961 to its delayed completion in April 1964. The stadium attracted an expansion franchise: the New York Mets, who played at Shea until 2008, when the stadium was demolished and replaced with Citi Field. The New York Jets football game squad also played its domicile games at Shea from 1964 until 1983, afterward which the team moved its dwelling house games to the Meadowlands Sports Complex in New Jersey.[43]

End of the Moses era [edit]

View of the 1964–1965 New York Globe'due south Fair as seen from the ascertainment towers of the New York State pavilion. The Off-white's symbol, the Unisphere, is the central paradigm.

Moses's reputation began to fade during the 1960s. Around this time, Moses's political apprehending began to fail him, equally he unwisely picked several controversial political battles he could not mayhap win. For case, his campaign against the free Shakespeare in the Park plan received much negative publicity, and his effort to destroy a shaded playground in Central Park to make way for a parking lot for the expensive Tavern-on-the-Light-green eatery earned him many enemies among the middle-form voters of the Upper Due west Side.

The opposition reached a climax over the demolition of Pennsylvania Station, which many attributed to the "development scheme" mentality cultivated past Moses[44] even though it was the impoverished Pennsylvania Railroad that was actually responsible for the demolition.[45] This casual destruction of 1 of New York's greatest architectural landmarks helped prompt many city residents to turn confronting Moses's plans to build a Lower Manhattan State highway, which would have gone through Greenwich Hamlet and what is now SoHo.[46] This plan and the Mid-Manhattan State highway both failed politically. One of his almost vocal critics during this fourth dimension was the urban activist Jane Jacobs, whose book The Death and Life of Great American Cities was instrumental in turning opinion against Moses's plans; the city regime rejected the expressway in 1964.[47]

A 1964 Parks Section map showing numerous Robert Moses projects, including several highways that went unbuilt or were simply partially completed.

Moses'due south power was further eroded by his association with the 1964 New York World'due south Fair. His projections for attendance of 70 million people for this event proved wildly optimistic, and generous contracts for fair executives and contractors made matters worse economically. Moses's repeated and forceful public denials of the fair'southward considerable financial difficulties in the face up of bear witness to the contrary somewhen provoked press and governmental investigations, which found accounting irregularities.[37] In his organization of the fair, Moses's reputation was now undermined past the same personal character traits that had worked in his favor in the past: disdain for the opinions of others and loftier-handed attempts to go his mode in moments of disharmonize past turning to the printing. The fact that the off-white was not sanctioned by the Bureau of International Expositions (BIE), the worldwide body supervising such events, would be devastating to the success of the effect.[48] Moses refused to accept BIE requirements, including a restriction against charging ground rents to exhibitors, and the BIE in turn instructed its member nations non to participate.[49] The United States had already staged the sanctioned Century 21 Exposition in Seattle in 1962. Co-ordinate to the rules of the organization, no one nation could host more one fair in a decade. The major European democracies, besides as Canada, Commonwealth of australia, and the Soviet Union, were all BIE members and they declined to participate, instead reserving their efforts for Expo 67 in Montreal.

After the World's Fair debacle, New York City mayor John Lindsay, along with Governor Nelson Rockefeller, sought to direct toll revenues from the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority's (TBTA) bridges and tunnels to cover deficits in the city's then financially ailing agencies, including the subway organization. Moses opposed this idea and fought to forestall information technology.[45] Lindsay then removed Moses from his post as the metropolis's main abet for federal highway money in Washington.

The legislature's vote to fold the TBTA into the newly created Metropolitan Transportation Dominance (MTA) could have led to a lawsuit past the TBTA bondholders. Since the bail contracts were written into country constabulary, it was unconstitutional to impair existing contractual obligations, as the bondholders had the correct of approval over such deportment. However, the largest holder of TBTA bonds, and thus agent for all the others, was the Hunt Manhattan Bank, headed then by David Rockefeller, the governor's blood brother. No suit was filed. Moses could take directed TBTA to become to court against the activity, only having been promised a role in the merged authority, Moses declined to claiming the merger. On March ane, 1968, the TBTA was folded into the MTA and Moses gave upwardly his post as chairman of the TBTA. He somewhen became a consultant to the MTA, but its new chairman and the governor froze him out—the promised function did not materialize, and for all practical purposes Moses was out of power.[43]

Moses had thought he had convinced Nelson Rockefeller of the demand for one final corking bridge project, a bridge crossing Long Island Sound from Rye to Oyster Bay. Rockefeller did not press for the project in the late 1960s through 1970, fearing public backlash amidst suburban Republicans would hinder his re-ballot prospects. A 1972 study found the bridge was fiscally prudent and could exist environmentally manageable (according to the comparatively low environmental impact parameters of that period), but the anti-development sentiment was now insurmountable and in 1973 Rockefeller canceled plans for the span.

The Power Broker [edit]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

Moses's paradigm suffered a further accident in 1974 with the publication of The Power Broker, a Pulitzer Prize–winning biography by Robert A. Caro. Caro's 1,200-page opus (edited down from 2,000 or so pages) showed Moses mostly in a negative calorie-free; essayist Phillip Lopate writes that "Moses's satanic reputation with the public can exist traced, in the main, to ... Caro's magnificent biography".[50] [14] For case, Caro describes Moses'south lack of sensitivity in the construction of the Cross-Bronx Motorway, and how he disfavored public transit. Much of Moses'south reputation is owing to Caro, whose book won both the Pulitzer Prize in Biography in 1975 and the Francis Parkman Prize (which is awarded by the Club of American Historians), and was named 1 of the 100 greatest non-fiction books of the twentieth century past the Modern Library.[49] [14] Upon its publication, Moses denounced the biography in a 23-page statement, to which Caro replied to defend his work's integrity.[51]

Caro'southward depiction of Moses's life gives him total credit for his early on achievements, showing, for example, how he conceived and created Jones Embankment and the New York Country Park arrangement, but likewise shows how Moses's desire for ability came to exist more of import to him than his earlier dreams. Moses is blamed for having destroyed more a score of neighborhoods past building xiii expressways across New York Metropolis and by building large urban renewal projects with picayune regard for the urban cloth or for human scale.[fourteen] Withal the author is more neutral in his central premise: the metropolis would have adult much differently without Moses. Other U.S. cities were doing the aforementioned matter as New York in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s; Boston, San Francisco, and Seattle, for instance, each built highways straight through their downtown areas.[14] The New York City architectural intelligentsia of the 1940s and 1950s, who largely believed in such proponents of the motorcar every bit Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, had supported Moses. Many other cities, similar Newark, Chicago, and St. Louis, also built massive, unattractive public housing projects.[52] [14] However, Caro also points out that Moses demonstrated racist tendencies.[53] These allegedly included opposing black World War II veterans to motility into a residential circuitous specifically designed for these veterans,[54] [ failed verification ] and purportedly trying to make swimming pool water common cold in order to drive abroad potential African American residents in white neighborhoods.[55]

People had come to see Moses every bit a dandy who overlooked public input, but until the publication of Caro's book, they had not known many details of his individual life—for instance, that his brother Paul had spent much of his life in poverty. Paul, whom Caro interviewed shortly before the former's death, claimed Robert had exerted undue influence on their female parent to change her will in Robert'southward favor shortly earlier her death.[14] Caro notes that Paul was on bad terms with their female parent over a long period and she may have changed the will of her own accord, and implies that Robert'south subsequent handling of Paul may accept been legally justifiable just was morally questionable.[14]

Decease [edit]

The crypt of Robert Moses

During the final years of his life, Moses concentrated on his lifelong love of swimming and was an active member of the Colonie Loma Health Club.

Moses died of heart disease on July 29, 1981, at the age of 92 at Good Samaritan Hospital in Westward Islip, New York.

Moses was of Jewish origin and raised in a secularist fashion inspired past the Upstanding Culture motility of the belatedly 19th century. He was a convert to Christianity[56] and was interred in a crypt in an outdoor community mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York Urban center post-obit services at St. Peter's past-the-Body of water Episcopal Church in Bay Shore, New York.

Legacy [edit]

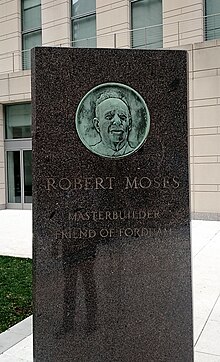

Diverse locations and roadways in New York State bear Moses'southward name. These include 2 state parks, Robert Moses State Park – Chiliad Islands in Massena, New York and Robert Moses State Park – Long Island, the Robert Moses Causeway on Long Island, and the Robert Moses Hydro-Electric Dam in Lewiston, New York. The Niagara Scenic Parkway in Niagara Falls, New York was originally named the Robert Moses Land Parkway in his honor; its name was changed in 2016. A hydro-electric power dam in Massena, New York likewise bears Moses's proper noun. Moses also has a school named subsequently him in North Babylon, New York on Long Island; there is too a Robert Moses Playground in New York City. There are other signs of the surviving appreciation held for him by some circles of the public. A statue of Moses was erected next to the Hamlet Hall in his long-fourth dimension hometown, Babylon Hamlet, New York, in 2003, as well as a bust on the Lincoln Eye campus of Fordham Academy, although information technology has since been removed from display and is currently in storage.

During his tenure as chief of the land park system, the state'due south inventory of parks grew to nearly 2,600,000 acres (one,100,000 ha). By the time he left office, he had built 658 playgrounds in New York City solitary, plus 416 miles (669 km) of parkways and 13 bridges.[57] Notwithstanding, the proportion of public benefit corporations is greater in New York than in any other U.S. state, making them the prime number mode of infrastructure edifice and maintenance in New York and bookkeeping for 90% of the state's debt.[58]

Appraisal [edit]

Criticism and The Power Broker [edit]

Moses was heavily criticized in Robert Caro'south 1974 award-winning biography The Power Broker. The book highlighted his exercise of starting big projects well across funding approved by the New York Land legislature, with the knowledge they would eventually have to pay for the rest to avoid looking like they had failed to review the project properly (a tactic known as fait accompli ). He was as well characterized every bit using his political ability to do good cronies, including a instance where he secretly shifted the planned road of the Northern Land Parkway large distances to avoid impinging on the estates of the rich, while telling owners of the family farms who lost country and sometimes their livelihood, that it was based on "technology considerations".[14] The book charged that Moses libeled other officials who opposed him, to have them removed from office, calling some of them communists during the Ruby Scare. The biography further notes that Moses fought against schools and other public needs in favor of his preference for parks.[14]

Moses's critics charge that he preferred automobiles over people. They point out that he displaced hundreds of thousands of residents in New York City, destroying traditional neighborhoods by building multiple expressways through them. These projects contributed to the ruin of the Southward Bronx and the amusement parks of Coney Island, acquired the difference of the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants Major League baseball teams, and precipitated the decline of public transport due to disinvestment and neglect.[14] His building of expressways hindered the proposed expansion of the New York City Subway from the 1930s well into the 1960s, considering the parkways and expressways that were built replaced, at least to some extent, the planned subway lines; the 1968 Plan for Activity, which was never completed, was hoped to counter this.[14] Other critics accuse that he precluded the utilise of public transit, which would have allowed non-automobile-owners to savour the elaborate recreation facilities he built.

Racism [edit]

Caro's The Power Broker accused Moses of building depression bridges across his parkways in order to "restrict the utilize of state parks by poor and lower-middle-grade families," who did not ain cars and would make it past bus, and of discouraging Black people, in particular, from visiting Jones Embankment, the centerpiece of the Long Isle land park system, past such measures equally making information technology difficult for Black groups to get permits to park buses fifty-fifty if they came anyway (by other roads), and assigning Black lifeguards to "afar, less developed beaches" instead.[35] While the exclusion of commercial vehicles, and the apply of low bridges where appropriate, were standard on before parkways, where they had been instituted for aesthetic reasons, Moses appears to have made greater use of low bridges, which his aide Sidney Shapiro said was done in order to make it more than difficult for time to come legislators to permit commercial vehicles.[59] [60] Caro's claims accept been questioned, given that buses do in fact make utilise of the parkways. Woolgar and Cooper refer to the claim about bridges every bit an "urban legend".[61] Joerges describes it as "counterfactual".[62]

Moses vocally opposed allowing Black war veterans to motion into Stuyvesant Town, a Manhattan residential development complex created to house World War II veterans.[54] [14] In response to the biography, Moses defended his forced displacement of poor and minority communities as an inevitable office of urban revitalization, stating "I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without moving people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs."[51]

Additionally, there were allegations that Moses selectively chose locations for recreational facilities based on the racial compositions of neighborhood, such as when he selected sites for eleven pools that opened in 1936. According to one author, Moses purposely placed some pools in neighborhoods with mainly white populations to deter African Americans from using them, while other pools intended for African Americans, such as the one in Colonial Park, at present Jackie Robinson Park, were placed in inconvenient locations.[63] Another author wrote that of 255 playgrounds built in the 1930s nether Moses'south tenure, two were in largely Black neighborhoods.[64] Caro wrote that shut assembly of Moses had claimed they could keep African Americans from using the Thomas Jefferson Puddle, in the then-predominantly white East Harlem, by making the water too common cold.[65] [55] However, no other source has corroborated the claim that heaters in any particular pool were deactivated or not included in the pool's pattern.[66]

Reappraisal [edit]

Some scholars accept attempted to rehabilitate Moses's reputation, contrasting the scale of works with the high cost and tiresome speed of public works in the decades post-obit his era. The pinnacle of Moses'south construction occurred during the economical duress of the Great Depression, and despite that era'due south woes, Moses'due south projects were completed in a timely mode, and take been reliable public works since—which compares favorably to the contemporary delays New York City officials have had redeveloping the Basis Zippo site of the quondam World Trade Center, or the delays and technical problems surrounding the Second Avenue Subway or Boston's Large Dig project.[67]

Three major exhibits in 2007 prompted a reconsideration of his paradigm amongst some intellectuals, equally they acknowledged the magnitude of his achievements. According to Columbia University architectural historian Hilary Ballon and assorted colleagues, Moses deserves better than his reputation as a destroyer. They argue that his legacy is more than relevant than e'er and that people take the parks, playgrounds and housing Moses congenital, now by and large bounden forces in those areas, for granted even if the one-time-style New York neighborhood was of no interest to Moses himself; moreover, were it not for Moses'due south public infrastructure and his resolve to cleave out more space, New York might not accept been able to recover from the bane and flight of the 1970s and '80s and become the economical magnet information technology is today.[68]

"Every generation writes its own history," said Kenneth T. Jackson, a historian of New York City. "It could exist that The Power Broker was a reflection of its time: New York was in problem and had been in decline for 15 years. At present, for a whole host of reasons, New York is entering a new fourth dimension, a time of optimism, growth and revival that hasn't been seen in half a century. And that causes united states to look at our infrastructure," said Jackson. "A lot of big projects are on the table once more, and it kind of suggests a Moses era without Moses," he added.[68] Politicians are as well reconsidering the Moses legacy; in a 2006 speech to the Regional Programme Association on downstate transportation needs, New York governor-elect Eliot Spitzer stated a biography of Moses written today might be chosen At Least He Got It Built: "That's what we demand today. A existent commitment to become things done."[69]

In popular civilization [edit]

- Moses is the bailiwick of a satirical vocal by John Forster entitled "The Ballad of Robert Moses", included on his 1997 album Helium.[70]

- Bulldozer: The Carol of Robert Moses (2017) is a stone musical, with book, music and lyrics past songwriter and composer Peter Galperin that dramatizes Moses'south evolution from a visionary idealist to a destroyer harming New York City.[71]

- An undead version of Robert Moses is the master antagonist of the get-go flavor of CollegeHumor's Dimension twenty: The Unsleeping City.[72]

- In season 3, episode 2 of the television series Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, "Kimmy's Roommate Lemonades", Kimmy is shown considering omnipresence at several New York City colleges with comedic names based on the city'south civilisation and history.[73] 1 was originally called "Robert Moses College for Whites", and its sign has been contradistinct by crossing out "Whites" and replacing it with the give-and-take "Anybody".[73]

- Moses is the discipline of a critical song by NYHC band Sick of It All entitled "Robert Moses was a racist", included on their 2018 album Wake the sleeping dragon!.[74]

- The band Bob Moses is named afterward Robert Moses.[75]

- A character named Moses Randolph and inspired past Robert Moses is portrayed by Alec Baldwin in the 2019 film Motherless Brooklyn.[76]

- At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many Boob tube commentators, politicians and others worked from their homes, The New York Times noted the frequent placement of The Ability Broker equally a background chemical element.[77]

- A play entitled "Straight Line Crazy" based on Moses' life opened at the Span Theatre, London in 2022, written by David Hare and starring Ralph Fiennes every bit Moses.

- The Hip-Hop group Armand Hammer released a vocal titled 'Robert Moses' on their album 'Haram' in 2021.

- The 2021 motion-picture show accommodation of West Side Story adds the historical context of New York City'southward urban gentrification in the 1950s. During the song "America", a grouping of Puerto Rican demonstrators announced, protesting their pending evictions, and one of them holds a sign condemning Robert Moses.[78]

See likewise [edit]

- Motorcar culture

- Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation

- Modernist architecture

- Transportation in New York City

- Urban sprawl

- M. Justin Herman

- Edward J. Logue

- Edmund Bacon (builder)

- Austin Tobin – Port Potency Executive Director

- Long Isle State Parkway Police

- New York State Park Police

- New York State Police force

Notes [edit]

- ^ Moses would telephone call himself a "coordinator" and was referred to in the media as a "chief builder".

References [edit]

- ^ Robert Caro, The Power Broker, 1975.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (July 30, 1981). "Robert Moses, Master Builder, is Dead at 92". The New York Times . Retrieved Nov xi, 2009.

- ^ "Mary Grady Moses, 77". The New York Times. September 4, 1993. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ a b Caro, Robert A. (July 22, 1974). "Annals of Ability". The New Yorker . Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ Sarachan, Sydney (January 17, 2013). "The legacy of Robert Moses". Demand to Know | PBS . Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Burkeman, Oliver (October 23, 2015). "The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York past Robert Caro review – a landmark study". The Guardian. London, Uk.

- ^ "'The Wrong Complexion For Protection.' How Race Shaped America'southward Roadways And Cities". NPR.org . Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ Campanella, Thomas J. (July 9, 2017). "Robert Moses and His Racist Parkway, Explained". Bloomberg City Lab. New York, NY: Bloomberg News.

- ^ "Robert Moses, Main Architect, is Dead at 92". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March v, 2016.

- ^ a b Caro 1974, pp. 29.

- ^ DeWan, George (2007). "The Chief Builder". Long Island History. Newsday. Archived from the original on December 11, 2006. Retrieved April iv, 2007.

- ^ Caro 1974, pp. 35.

- ^ "Robert Moses".

- ^ a b c d due east f m h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w 10 y Caro 1974.

- ^ "Moses Resigns State Position". Cornell Daily Lord's day. Ithaca, NY. December 19, 1928. p. 8.

- ^ Gutfreund, Owen. "Moses, Robert". Anb.org. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City . Routledge. pp. 472. ISBN978-0-415-25225-6.

- ^ "New York City Parks Commissioners : NYC Parks". world wide web.nycgovparks.org . Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ "Robert Moses |". www.nypap.org . Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ "Taconic State Parkway". NYCRoads.com . Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ Leonard, Wallock (1991). The Myth of The Main Builder. Journal of Urban History. p. 339.

- ^ Caro 1974, pp. 106, 260.

- ^ Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Patrick; Mellins, Thomas (1987). New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanism Betwixt the Two World Wars. New York: Rizzoli. p. 717. ISBN978-0-8478-3096-ane. OCLC 13860977.

- ^ a b c Caro, Robert (1974). The Ability Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. New York: Knopf. p. 456. ISBN978-0-394-48076-3. OCLC 834874.

- ^ "23 Bathing Pools Planned past Moses; Ix to Be Begun in a Month to See Shortage of Facilities Acquired by Pollution". The New York Times. July 23, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ "Public Swimming Facilities in New York City" (PDF) (Press release). New York Urban center Section of Parks and Recreation. July 23, 1934. p. 3 (PDF p. 30). Retrieved January six, 2021.

- ^ "City to Construct nine Pools To Provide Safe Swimming". New York Daily News. July 23, 1934. p. 8. Retrieved Baronial 18, 2019 – via newspapers.com

.

. - ^ a b "History of Parks' Swimming Pools". New York City Section of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved Jan 15, 2021.

- ^ Shattuck, Kathryn (August 14, 2006). "Big Chill of '36: Show Celebrates Giant Depression-Era Pools That Cool New York". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Park Work Is Begun on 2 Bathing Pools; Structure Under Manner at High Bridge and Hamilton Fish – 7 Others to Be Started Soon" (PDF). The New York Times. October 4, 1934. p. 48. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved Jan xiii, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Revisiting The 11 Pools Whose Gala Openings Defined 1936". Curbed NY. August 29, 2013.

- ^ Gutman, M. (2008). "Race, Place, and Play: Robert Moses and the WPA Swimming Pools in New York Metropolis". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 67 (4): 532–561. doi:10.1525/jsah.2008.67.4.532. JSTOR 10.1525/jsah.2008.67.4.532.

- ^ Brozan, Nadine (July 30, 1990). "A Crumbling Puddle Divides a Neighborhood". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Schuster, Karla (Baronial 3, 2007). "After 71 years Astoria Puddle is among 10 outdoor public pools that the city is designating as landmarks". Newsday. ProQuest 280156824. Retrieved May 12, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Caro 1974, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Doig, Jameson W. (November 15, 2002). Empire on the Hudson . Columbia Academy Printing. ISBN978-0-231-07677-seven.

- ^ a b Carion, Carlos. "Robert Moses" (PDF). Nexus.umn.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 26, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel (I-478)". Nycroads.com. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "Queens-Midtown Tunnel". NYCRoads.com . Retrieved August one, 2010.

- ^ Mesh, Aaron (November 5, 2014). "Feb. 4, 1974: Portland kills the Mount Hood Expressway". Willamette Calendar week. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

Every great civilization has an origin story. For modern Portland, information technology is an exodus from Moses. That's Robert Moses, the master builder of New York City's grid of expressways and bridges who brought the Big Apple its machine commuters, smog and sprawl. In 1943, the city of Portland hired Moses to design its urban future. Moses charted a highway loop effectually the city's core with a web of spur freeways running through neighborhoods. The city and land embraced much of the program. The loop Moses envisioned became Interstate 405 every bit it links with I-5 southward of downtown and runs due north across the Fremont Bridge.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1979). "Eccentricities". Isaac Asimov'due south Book of Facts. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. p. 105. ISBN978-0-448-15776-4.

- ^ Fetter, Henry D. (Winter 2008). "Revising the Revisionists: Walter O'Malley, Robert Moses, and the End of the Brooklyn Dodgers". New York History (New York State Historical Association). Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Murphy, Robert (June 24, 2009). "OMalley-vs-Moses". Huffington Post.

- ^ Lopate, Phillip (March xiii, 2007). "Rethinking Robert Moses". Metropolis Magazine. Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved Oct 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Kay, Jane Holtz (Apr 24, 1989). "Robert Moses: The Master Builder" (PDF). The Nation. 248 (sixteen): 569. Archived from the original (PDF) on July xvi, 2004. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ "Environmental and Urban Economics: Robert Moses: New York Urban center's Master Builder?". Greeneconomics.blogspot.com. May 6, 2007. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ "The Next American System — The Master Builder (1977)". PBS. February iii, 2010.

- ^ "Robert Moses: Long Island's Main Architect". YouTube. Archived from the original on November fourteen, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ a b "Robert Moses". Learn.columbia.edu. Retrieved Dec 24, 2014.

- ^ Lopate, Phillip (February eleven, 2007). "A Boondocks Revived, a Villain Redeemed". The New York Times. Section 14, col. ane. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Boeing, K. (2017). "We Live in a Motorized Civilization: Robert Moses Replies to Robert Caro". SSRN: 1–13. arXiv:2104.06179. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2934079. S2CID 164717606. Retrieved Baronial thirteen, 2017.

- ^ Glaeser, Edward (January 19, 2007). "Great Cities Demand Great Builders". The New York Dominicus . Retrieved October nine, 2010.

- ^ Caro 1974, pp. 510, 514.

- ^ a b Chaldekas, Cynthia (March 16, 2010). "Wrestling with Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took on New York'southward Principal Builder and Transformed the American City". New York Public Library . Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Powell, Michael (May 6, 2007). "A Tale of Two Cities". The New York Times . Retrieved August ane, 2010.

As for the pool-cooling, Mr. Caro interviewed Moses's assembly on the record ("You can pretty well keep them out of whatever pool if you keep the h2o cold plenty," he quotes Sidney M. Shapiro, a close Moses aide, as saying).

- ^ Purnick, Joyce (Baronial i, 1981). "Legacy of Moses Hailed". The New York Times. Section 2, col. 1, p. 29. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ "Robert Moses, Master Builder, is Expressionless at 92". Nytimes.com. July thirty, 1981. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ "New York's 'shadow regime' debt rises to $140 billion". The Post-Standard. Syracuse. Associated Printing. September 2, 2009. Retrieved Dec 16, 2010.

- ^ Caro 1974, pp. 952.

- ^ Campanella, Thomas. "How Low Did He Go?". Citylab . Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ Woolgar, Steve; Cooper, Geoff (1999). "Do Artefacts Accept Ambivalence? Moses' Bridges, Winner's Bridges and Other Urban Legends in S&TS". Social Studies of Science. 29 (3): 433–449. doi:10.1177/030631299029003005. ISSN 0306-3127. JSTOR 285412. S2CID 143679977. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Joerges, Bernward (June 1, 1999). "Practice Politics Have Artefacts?". Social Studies of Science. 29 (3): 411–431. doi:x.1177/030631299029003004. hdl:10419/71061. ISSN 0306-3127. S2CID 145677328. Retrieved Nov 17, 2021.

- ^ Wiltse, Jeff (2009). Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America. University of Due north Carolina Printing. p. 140. ISBN978-0-8078-8898-eight . Retrieved Jan 10, 2021.

- ^ Riess, Steven A. (1991). Metropolis Games: The Evolution of American Urban Club and the Ascension of Sports. An Illini book. University of Illinois Press. p. 148. ISBN978-0-252-06216-ii.

- ^ Caro 1974, pp. 512–514.

- ^ Gutman, Marta (Nov 1, 2008). "Race, Identify, and Play: Robert Moses and the WPA Swimming Pools in New York City". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. Academy of California Press. 67 (iv): 538. doi:10.1525/jsah.2008.67.iv.532. ISSN 0037-9808.

- ^ Glaeser, Edward (January 19, 2007). "Great Cities Need Great Builders". The New York Sun . Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Pogrebin, Robin (January 28, 2007). "Rehabilitating Robert Moses". The New York Times. p. one, Section 2, col. iii. Retrieved August i, 2010.

- ^ Spitzer, Eliot (May 5, 2006). "Downstate Transportation Issues Voice communication" (PDF). Regional Programme Association. Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved Feb 15, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "John Forster: the Ballad of Robert Moses". AllMusic. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Ryan Leeds (December xviii, 2017). "If You Build It, They Will Come: "Bulldozer, the Ballad of Robert Moses."". thebroadwayblog.com . Retrieved Jan five, 2018.

- ^ "Dimension 20 (TV Series 2018– ) – IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ a b Pape, Allie (May xix, 2017). "Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Recap: Furiosity". Vulture. New York, NY: New York Media.

- ^ "Ill of It All: Robert Moses was a racist". Discogs. Retrieved April nineteen, 2019.

- ^ "Vancouver duo Bob Moses on going from a parking lot to the Grammy Awards".

- ^ Denninger, Lindsay (November two, 2019). "There's Actually Some Truth Behind Motherless Brooklyn's Moses Randolph". Refinery29 . Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ Rubinstein, Dana (May 28, 2020). "Lights. Camera. Makeup. And a Carefully Placed 1,246-Page Volume". The New York Times. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ Hornaday, Ann. "'Due west Side Story' is an urgent, utterly beautiful revival". Washington Mail. Retrieved Jan 17, 2022.

Bibliography [edit]

- Ballon, Hilary (2007). Robert Moses and the modern city : the transformation of New York. New York: W.West. Norton & Co. ISBN978-0-393-73243-6. OCLC 76167277.

- Berman, Marshall (1988). All that is solid melts into air : the feel of modernity. New York, Due north.Y., U.s.a.A: Viking Penguin. ISBN978-0-14-010962-7. OCLC 16923119.

- Caro, Robert (1974). The Power Banker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. New York: Knopf. ISBN978-0-394-48076-iii. OCLC 834874.

- Christin, Pierre (2014). Robert Moses : Chief Architect of New York Metropolis. London: Nobrow. ISBN978-1-907704-96-3. OCLC 875240382.

- Christin, Pierre; Balez, Olivier (2018). Robert Moses: The Master Builder of New York City. London: Nobrow. ISBN978-1-910620-36-half dozen.

- Doig, Jameson W. (1990). "Regional Conflict in the New York Metropolis: the Legend of Robert Moses and the Power of the Port Authority". Urban Studies. SAGE Publications. 27 (2): 201–232. doi:ten.1080/00420989020080181. ISSN 0042-0980. S2CID 146841751.

- Krieg, Joann (1989). Robert Moses : single-minded genius. Interlaken, N.Y: Middle of the Lakes Pub. ISBN978-i-55787-041-4. OCLC 18961485.

- Lewis, Eugene (1980). Public entrepreneurship : toward a theory of bureaucratic political power : the organizational lives of Hyman Rickover, J. Edgar Hoover, and Robert Moses. Bloomington: Indiana Academy Press. ISBN978-0-253-17384-3. OCLC 6581080.

- Moses, Robert (1970). Public Works: A Dangerous Trade . McGraw-Hill.

- Rogers, Cleveland (January ane, 1939). "Robert Moses". The Atlantic.

- Rodgers, Cleveland (1952). Robert Moses: Builder for Democracy. Holt.

- Vidal, Gore (October 17, 1974). What Robert Moses Did to New York Metropolis. New York Review of Books.

Other sources [edit]

External links [edit]

- Robert Moses Papers (MS 360). Manuscripts and Athenaeum, Yale University Library.[1]

- A motion picture clip "Longines Chronoscope with Robert Moses (Feb xi, 1953)" is available at the Net Archive

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Moses

0 Response to "Moses Get Ready to Part the Seas Again Cause Shit Is About to Get Wet ïâ»â¿"

Post a Comment